Trees are a very important part of our urban landscapes. They provide us with shade, clean the air, prevent soil erosion, help combat global warming, and look great, too! Trees can be injured and the causes are many, including broken branches, animals, insects, fire, and careless equipment operators. Two common winter injuries are sunscald and snow load damage.

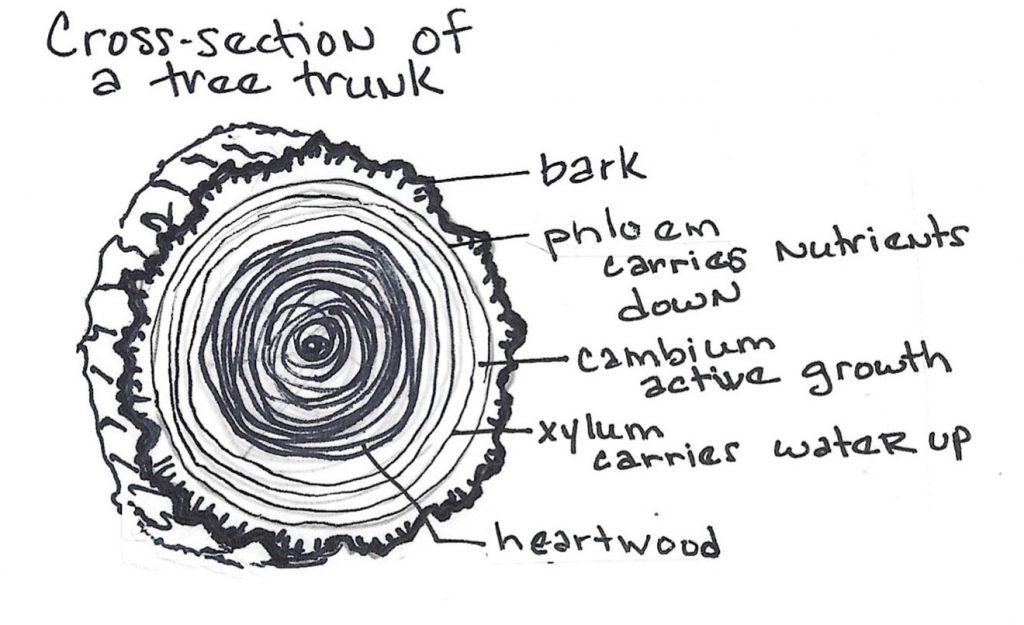

To understand how a tree responds to an injury, first let me describe how a tree functions. The trunk and branches work like a large set of straws moving water and nutrients between the roots and the leaves. A cross section of the trunk looks like this:

The outer layer, the bark, is simply a protective layer. Various trees have bark adaptations to protect against pests, mammals, fire, or cold. The next layer is the phloem (FLOW-em). This is where the sap (sugar water) travels down the tree to feed the root zone. The bark is actually the last few years’ growth of phloem which has died.

Cambium is a very thin layer next to the phloem. The cambium is the only region of actively growing and dividing cells. Depending on nutrient and water availability, the cambium will grow more or less in any given year. This is what makes the rings in the tree trunk. The cambium produces phloem cells on one side and xylem cells on the other.

Moving toward the center of the trunk or branch, the next layer inside the tree is called xylem. The xylem is the last few years of cambium cells. These thick walled cells carry water and minerals up the tree from the roots to the leaves.

Finally, at the center of the trunk is the heartwood. After a few years, the xylem fills in with resin-like material and no longer works to transport water. The cells, however, become stronger in the process giving the tree even more rigidity.

A tree’s response to an injury, of course, depends on the nature of the injury. When bark is punctured or removed, the exposed phloem cells are vulnerable to fungi and bacteria and environmental stress. The phloem cells die off, forming new bark to cover the injury. Depending on the thickness of the bark, the injury may always be visible as is the case of a pocket knife engraving initials in an Aspen tree.

If the injury is more severe, such as sunscald or a broken branch, the tree will seal off the injury rather than heal it. First, the chemistry of the surrounding wood changes to ward off bacteria and other decaying organisms. This is called the reaction zone. Next, the cambium cells near the injury elongate, creating a callus or a raised area around the wound. These two processes together are called compartmentalization. Over time, the elongated cells gradually cover the exposed heartwood.

A severe injury like this disrupts the plumbing systems moving water and nutrients around the tree. If less than 25% of the phloem is destroyed, the tree will likely survive although it may be stunted, or grow lopsided. When the phloem is disrupted at 75-100% of the circumference it is considered girdling and s typically fatal. Girdling can be caused by a wire tie that wasn’t removed when the tree was planted, a tree strap that was left on for too long, or a porcupine chewing all the way around the trunk.

Tree injuries can take years to completely seal over. A tree doesn’t really “heal” from a wound, it grows around it. Therefore, it’s important to protect our trees from injury.

For more information on caring for your trees this winter, check out this previous blog post: Tips for Healthier Trees

To learn more about sunscald, see this information sheet from CSU extension: Sunscald of Trees

Fort Collins Nursery has good information in their blog post: Protect trees from heavy snow